Viral infections(a) HHV-6a virus

|

Important lecture by Dr. Martin Lerner on the role of viruses in ME / CFS. Click on links to view videos. |

Dr. Martin Lerner The Treatment Center for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome which has successfully treated thousands of ME / CFS patients. Dr Martin Lerner has the following credentials: Medical doctor with 40 years experience. Certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and is an Infectious Disease Specialist. Residency, Internal Medicine, Harvard Medical Services. Boston City Hospital and Barnes Hospital, St. Louis, MO. Washington University School of Medicine, M.D. Two Years, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Epidemiology Unit. Three years research fellow in infectious diseases at the Thorndike Memorial Laboratory, Boston City Hospital and Harvard Medical School under the direction of *Dr. Maxwell Finland, (founder of subspecialty infectious diseases). Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and Professor of Internal Medicine at Wayne State University School of Medicine, 1963-1982. Established a clinical virology laboratory and trained 33 physicians in the subspecialty of infectious diseases, Wayne State University, 1963-1982. |

-

“Two disorders of significant importance, MS and CFS, appear to be associated with HHV-6 infection…the data presented here show that both MS and CFS patients tend to carry a higher rate of HHV-6 infection or reactivation compared to normal controls. This immunological and virological data supports a role of HHV-6 in the symptomatology of these diseases…Based on biological, immunological and molecular analysis, the data show that HHV-6 isolates from 70% of CFS patients were Variant A…Interestingly, the majority of HHV-6 isolates from MS patients were Variant B…These data demonstrate that the CFS patients exhibited HHV-6 specific immune responses…Seventy percent of the HHV-6 isolates from CFS patients were Variant A, similar to those reported in AIDS…It has already been shown that active HHV-6 infection in HIV-infected patients enhanced the AIDS disease process. We suspect that the same scenario is occurring in the pathogenesis of MS and CFS…The immunological data presented here clearly shows a significantly high frequency of HHV-6 reactivation in CFS and MS patients. We postulate that active HHV-6 infection is a major contributory factor in the aetiologies of MS and CFS” (DV Ablashi, DL Peterson et al. Journal of Clinical Virology 2000:16:179-191).

-

The work of psychiatrists - Dr. Thomas Henderson and Dr. William Pridgen

- Valacyclovir treatment of chronic fatigue in adolescents. Henderson TA. Adv Mind Body Med. 2014 Winter;28(1):4-14.

- The Role of Antiviral Therapy in Chronic Fatigue Treatment

- Treatment Resistant Depression or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Child Psychiatrist Finds Success With Antivirals

- Doctors on Missions

-

“Over the last decade a wide variety of infectious agents has been associated with CFS by researchers from all over the world. Many of these agents are neurotrophic and have been linked to other diseases involving the central nervous system (CNS)…Because patients with CFS manifest a wide range of symptoms involving the CNS as shown by abnormalities on brain MRIs, SPECT scans of the brain and results of tilt-table testing, we sought to determine the prevalence of HHV-6, HHV-8, EBV, CMV, Mycoplasma species, Chlamydia species and Coxsackie virus in the spinal fluid of a group of patients with CFS. Although we intended to search mainly for evidence of actively replicating HHV-6, a virus that has been associated by several researchers with this disorder, we found evidence of HHV-8, Chlamydia species, CMV and Coxsackie virus in (50% of patient) samples…It was also surprising to obtain such a relatively high yield of infectious agents on cell free specimens of spinal fluid that had not been centrifuged” (Susan Levine. JCFS 2002:9:1/2:41-51).

- The destructive power of HHV-6a virus

- HHV-6a is able to infect and kill natural killer cells. Lusso, Paolo et al.; "Infection of Natural Killer Cells by Human Herpesvirus 6"; Nature 349:533, February 7, 1991.

- HHV-6a is able to infect and kill CD4 (T4) cells. Lusso, P. et al.; "Productive Infection of CD4-Positive and CD8-Positive Mature Human T Cell Populations and Clones by Human Herpesvirus 6"; Journal of Immunology 147(2):685, July 15, 1991.

- HHV-6a can cause other immune system cells (like CD8 cells) to express the CD4 cell surface antigen. Lusso, P. et al; "Induction of CD4 and Susceptibility to HIV-1 Infection in Human CD98-Positive T Lymphocytes by Human Herpesvirus 6"; Nature 349:533, February 7, 1991.

- HHV-6a destroys the B-cells of the immune system at a rapid rate. This has been found in research carried out by Robert Gallo MD of the NIH in the USA and research by virologist Berch Henry, Nevada. This research is cited in the book 'Oslers Web', by Hillary Johnson, Penguin Books 1997

- HHV-6a can infect a wide variety of organ tissues (besides immune system cells), including brain, spinal cord, lung, lymph node, heart, bone marrow, liver, kidney, spleen, tonsil, skeletal muscle, adrenal glands, pancreas, and thyroid. Knox, K.K. and D.R. Carrigan; "Disseminated Active HHV-6a Infections in Patients With AIDS"; The Lancet 343:577, March 5, 1994.

- HHV-6a has been found to be closely associated with Kaposi's sarcoma, and suggested as a possible causitive agent of this "AIDS"-related cancer. Bovenzi, P. et al.; "Human Herpesvirus 6 (Variant A) in Kaposi's Sarcoma"; The Lancet 341:1288, May 15, 1993.

- HHV-6a has been associated with thrombocytopenia, a blood clotting disorder common in "AIDS" patients. Kitamura, K. et al.; "Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura After Human Herpesvirus 6 Infection"; The Lancet 344:830, September 17, 1994.

- HHV-6a appears to cause graft-versus-host disease, an immune disorder that develops after transplant surgery (particularly after bone marrow transplantation). Cone, R.W. et al.; "Human Herpesvirus 6 in Lung Tissue From Patients With Pneumonitis After Bone Marrow Transplantation"; New England Journal of Medicine 329:156, July 15, 1993.

- HHV-6a can infect other species; most notably, it has been found in 100 percent of some populations of African green monkeys. Higashi, K. et al.; "Presence of Antibody to HHV-6 In Monkeys"; J. Gen. Virol. 70:3171, 1989.

- HHV-6a can cause fatal, disseminated infections. Knox and Carrigan, op cit.

- HHV-6a can cause fatal pneumonitis (lung infection). R.W. Cone, op cit.

- HHV-6a can cause fatal liver failure. Asano, Y. et al.; "Fatal Fulminate Hepatitis in an Infant With Human Herpesvirus-6 Infection"; The Lancet April 7, 1990.

- HHV-6a can cause hepatitis, a sometimes-fatal liver infection. Y. Asano et al., ibid.

- HHV-6a is associated with the development of brain lesions. Buchwald, D. et al.; "A Chronic, 'Postinfectious' Fatigue Syndrome Associated With Benign Lymphoproliferation, B-Cell Proliferation, and Active Replication of Human Herpesvirus-6"; Journal of Clinical Immunology 10:335, 1990.

- HHV-6a is associated with a particular type of skin rash, or dermatitis, that occurs frequently following bone marrow transplantation. Michel, D. et al.; "Human Herpesvirus 6 DNA in Exanthematous Skin in BMT Patient"; The Lancet 344:686, September 3, 1994.

- HHV-6a is spread through saliva. Levy, J. et al.;"Frequent Isolation of HHV-6 From Saliva and High Seroprevalence of the Virus in the Population"; The Lancet, May 5, 1990.

- HHV-6a has been found to be associated with Hodgkin's lymphoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia, African Burkitts lymphoma, and sarcoidosis, as well as "AIDS" and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Lusso, P. et al.; "In Vitro Cellular Tropism of Human B-Lymphotropic Virus(Human Herpesvirus-6)"; Journal of Experimental Medicine 167:1659, May 1988.

- The two variants of HHV-6, Variant A and Variant B, appear to cause very different symptoms. Variant B seems to be associated with mild, childhood infection and disease; Variant A is found in immunocompromised adults with illnesses like "AIDS," cancer, and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Dewhurst, S.W. et al.; "Human Herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) Variant B Accounts for the Majority of Symptomatic Primary HHV-6 infections in a Population of U.S. Infants"; Journal of Clinical Microbiology, February 1993.

- HHV-6a's growth is stopped by the experimental drug Ampligen. Ablashi, D.V. et al.; Ampligen Inhibits In Vitro Replication of HHV-6"; Abstract from CFS conference, Albany, NY, October 2-4, 1992

- When HHV-6a's growth is stopped by the experimental drug Ampligen in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients, their symptoms resolve. (In a trial published in 1987, the same appeared to be true for "AIDS" patients treated with Ampligen.) Strayer, D.R. et al.; "A Controlled Clinical Trial With a Specifically Configured RNA Drug, Poly(I):Poly(C12U), in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome";Clinical Infectious Diseases, January 1994.

- HHV-6a has been suggested as a "cofactor" in the

development of "AIDS." P. Lusso and R.C. Gallo;

"Human Herpesvirus 6 in AIDS"; The Lancet 343:555, March

5, 1994.

Effects of HHV-6a virus compiled by Neenyah Ostrom

- Association of Active Human Herpesvirus-6, -7 and Parvovirus B19 Infection with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Svetlana Chapenko, Angelika Krumina, Inara Logina, Santa Rasa, Maksims Chistjakovs, Alina Sultanova, Ludmila Viksna, and Modra Murovska. Advances in Virology. Volume 2012, Article ID 205085, 7 pages

- Nicolson et al showed that multiple co-infections (Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, HHV-6) in blood of chronic fatigue syndrome patients are associated with signs and symptoms: “Differences in bacterial and/or viral infections in (ME)CFS patients compared to controls were significant…The results indicate that a large subset of (ME)CFS patients show evidence of bacterial and/or viral infection(s), and these infections may contribute to the severity of signs and symptoms found in these patients” (Nicolson GL et al. APMIS 2003:111(5):557-566).

- Anti-pathogen and immune system treatments. Treatment of 741 italian patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. U. TIRELLI, A. LLESHI, M. BERRETTA, M. SPINA, R. TALAMINI, A. GIACALONE. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2013; 17: 2847-2852

- There was evidence for ongoing infections with herpes viruses. A subset of patients (those with onset associated with EBV and those with recurrent herpes lesions) who improved on valaciclovir. She recommends trying a course in these patients. Some patients may have ongoing EBV activation. (Invest in ME Scientific Conference, 2013 Professor Carmen Scheibenbogen, Berlin,Germany)

- Okadaic acid-like toxin in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: hypothesis for toxin-induced pathology, immune dysregulation, and transactivation of herpesviruses; Mitchell TM; Med Hypotheses. 1996 Sep;47(3):217-25. Herpes virus infections are of interest to ME / CFS patients and research.

- In his Summary of the Viral Studies of CFS, Dr Dharam V Ablashi concluded: “The presentations and discussions at this meeting strongly supported the hypothesis that CFS may be triggered by more than one viral agent…Komaroff suggests that, once reactivated, these viruses contribute directly to the morbidity of CFS by damaging certain tissues and indirectly by eliciting an on-going immune response”(Clin Inf Dis 1994:18 (Suppl 1):S130-133). It is recommended that the entire 167-page Journal be read

- The Putative Role of Viruses, Bacteria, and Chronic Fungal Biotoxin Exposure in the Genesis of Intractable Fatigue Accompanied by Cognitive and Physical Disability. Morris et al. 2015

- Vojdani A

,

Lapp CW

. Interferon-induced proteins are elevated in blood samples of

patients with chemically or virally induced chronic fatigue syndrome. Immunopharmacol

Immunotoxicol. 1999 May;21(2):175-202. PMID: 10319275

Certain toxic chemicals and certain viruses produce the same kinds of inflammatory effects and defects in 2-5A Synthetase and Protein Kinase RNA (PKR)). Anti IFN beta inhibited the reactions.

-

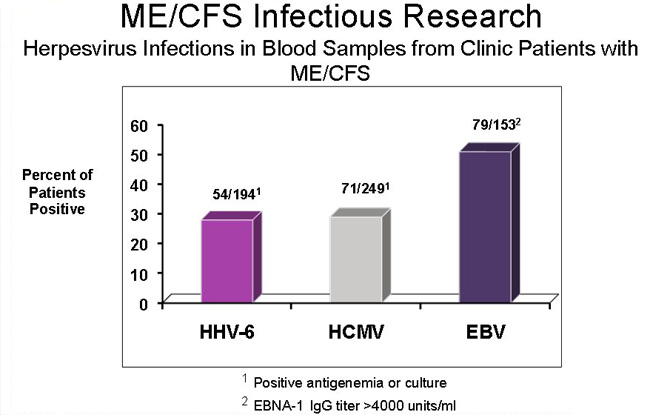

Ablashi and Loomis pointed out that an analysis of studies of HHV-6 in (ME)CFS differentiated between active and latent virus, with 83% being positive (Assessment and Implications of Viruses in Debilitating Fatigue in CFS and MS Patients. Dharam V Ablashi et al. HHV-6 Foundation, Santa Barbara, USA. Submission to Assembly Committee/Ways & Means, Exhibit B1-20, submitted by Annette Whittemore 1st June 2005).

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: clinical condition associated with immune activation. Lancet, 1991, 338, 707-712. AL Landay.

- The Virus Within

By Nicholas Regush explore the role of HHV-6a virus in ME / CFS and other diseases, and provides many references.

- Freeman ML, Burkum CE, Jensen MK, Woodland DL, Blackman MA(2012), "γ-Herpesvirus Reactivation Differentially Stimulates Epitope-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses", Immunology, 2012 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102787,

- Richard B. Schwartz et al., ' SPECT Imaging of the Brain: Comparison of Findings in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, AIDS Dementia Complex, and Major Unipolar Depression ' American Journal of Roentgenology 162 (April 1994): 943-51

- "CFS patients with active HHV6 infection were shown to have activation of coagulation and are hypercoagulable. This may be a significant factor in CFS contributing to many symptoms." J. Brewer, research paper presented to the AACFS 5th International Research, Clinical and Patient Conference, 2001

- Human herpesvirus-6-specific interleukin 10-producing CD4+ T cells suppress the CD4+ T-cell response in infected individuals Wang F, Yao K, Yin QZ, Zhou F, Ding CL, Peng GY, Xu J, Chen Y, Feng DJ, Ma CL, Xu WR.. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50(10):787-803.

- Jason LA, Sorenson M, Porter N, Belkairous N (2010), "An Etiological Model for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", Neuroscience & Medicine, 2011, 2, 14-27, PMID: 21892413

- Jones JF et al. J Med Virol 1991; 33: 151

-

Carver LA et al. Military Medicine 1994; 159: 580

-

HYPOTHESIS: A UNIFIED THEORY OF THE CAUSE OF CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

A. Martin Lerner, Marcus Zervos, Howard J. Dworkin, Chung Ho Chang, and William O'Neill

Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice, 1997;6:239-243 -

Presence of Viral Protein 1 (VP1)

"There are no tests to confirm a diagnosis, although 60% of sufferers will have a specific protein in their blood called viral protein 1, (VP1)."

Susan Clark, www.whatreallyworks.co.uk -

Findings and Testimony of Burke A. Cunha, MD., chief, infectious disease division, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, N.Y., USA.

"But the most consistent lab evidence that we look for are elevations of coxsackie B-titers and elevations of HHV-6 titers in combination with the decrease in the percentage of natural killer T cells," Cunha explained. "If the patient has two or three of these abnormalities in our study center, then he or she fits the laboratory criteria for chronic fatigue. Nearly all patients with crimson crescents have two out of three of these laboratory abnormalities," he said. - Stephen F. Josephs et al., 'HHV6 Reactivation in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome' , Lancet 337 (8753) June 1 1991: 1346-47

Roert J. Suhadolnik et al., ' Changes in the 2-5A Synthetase/Rnase L Antiviral Pathway in a Controlled Clinical Trial with Poly(I)-Poly(C12U) in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ' In Vivo 8 (1994): 599-604.

"Poly(I)-Poly(C12U)" is the molecular name for Ampligen-

Barnes, Deborah; "Mystery Disease at Lake Tahoe Challenges Virologists and Clinicians"; Science 234:541, 1986.

- Relationships Between Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type II (HTLV-2) and Human Lymphotropic Herpes viruses in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Project funded by The National CFIDS Foundation, Inc.; Needham, Massachusetts

-

Beldekas, John, Jane Teas, and James R. Hebert; "African Swine Fever Virus and AIDS"; The Lancet, March 8, 1986.

-

Buchwald, Dedra et al.; "A Chronic Postinfectious Fatigue Syndrome Associated With Benign Lymphoproliferation, B-Cell Proliferation, and Active Replication of Human Herpesvirus-6"; Journal of Clinical Immunology 10(6):335, 1990.

-

Marion Poore et al., ' An Unexplained Illness in West Otago ' The New Zealand Medical Journal 97, no.757 (1984): 351-354

-

Carter, William et al.; "Clinical, Immunological, and Virological Effects of Ampligen, a Mismatched Double-Stranded RNA, in Patients With AIDS or AIDS-Related Complex"; The Lancet, p. 1228, 1987.

Carter, W.; Interview in "Experimental Drug Held Effective for Chronic Fatigue, Immune Dysfunction"; American Society for Microbiology Conference Journal, September 29-October 2, 1991.

-

DeLuca, et al.: HHV-6 and HHV-7 in CFS. J Clin Micro 1995;33:1660-61.

-

Yalcin, et al.: Prevalence of HHV-6 variants A and B in patients with CFS. Microbiol Immunol 1994;38:587-90.

-

Hypothesis: A unified theory of the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome. A. Martin Lerner, Marcus Zervos, Howard J. Dworkin, Chung Ho Chang, and William O'Neill. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice, 1997;6:239-243

-

New Cardiomyopathy: Pilot Study of Intravenous Ganciclovir in a Subset of the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Infectious Disease in Clinical Practice, 1997;6:110-117

-

Sairenji, et al.: Antibody responses to Epstein-Barr virus, HHV-6 and HHV-7 in patients with CFS. Intervirology 1995;38:269-73

-

Frequent HHV-6 reactivation in multiple sclerosis (MS) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients.

Authors: Ablashi DV, Eastman HB, Owen CB, Roman MM, Friedman J, Zabriskie JB, Peterson DL, Pearson GR, Whitman JE. Journal of Clinical Virology (ISSN 1386-6532) 2000 May 1;16(3):179-191 -

Persistent Active Human Herpesvirus Six (HHV-6) Infections In Patients With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Konstance K Knox, Ph.D.; Joseph H. Brewer, M.D. and Donald R. Carrigan, Ph.D. Institute for Viral Pathogenesis and Wisconsin Viral Research Group; Milwaukee, Wisconsin1 and St. Luke's Hospital; Kansas City, Missouri. Presented at the Fourth International American Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Conference October 12-14, 1998.

-

Dynamics of Chronic Active Herpesvirus-6 Infection in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Data Acquisition for Computer Modeling

Authors: Krueger GR, Koch B, Hoffmann A, Rojo J, Brandt ME, Wang G, Buja LM.

Affiliation: Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Texas-Houston Medical School, 6431 Fannin St, MSB 2.246, Houston, Texas 77030, USA.

04-02-2002 Journal: In Vivo 2001 Nov-Dec;15(6):461-5 -

Moore, Patrick S. and Yuan Chang; "Detection of Herpes virus-Like DNA Sequences in Kaposi's Sarcoma in Patients With and Those Without HIV Infection"; The New England Journal of Medicine 332:1181, May 4, 1995.

- Cunha, Burke A.; "Crimson Crescents--A Possible Association With the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome"; Annals of Internal Medicine 116(4), February 15, 1992.

-

Su, Ih-Jen et al.; "Herpesvirus-Like DNA Sequence in Kaposi's Sarcoma From AIDS and non-AIDS Patients in Taiwan"; The Lancet 345:722, March 18, 1995.

-

Boshoff, Chris et al.; "Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpes virus in HIV-Negative Kaposi's Sarcoma"; The Lancet 345:1043, April 22, 1995.

-

Di Luca, Dario et al.; "Human Herpesvirus 6 and Human Herpesvirus 7 in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome"; Journal of Clinical Microbiology 33:1660, June 1995.

-

Lusso, Paolo, Mauro S. Mainati, Alfredo Garzino-Demo, Richard W. Crowley, Eric O. Long, and Robert C. Gallo; "Infection of Natural Killer Cells by Human Herpesvirus 6"; Nature 862:459, April 1, 1993.

-

Lusso, P. et al.; "Productive Infection of CD4-Positive and CD8-Positive Mature Human T Cell Populations and Clones by Human Herpesvirus 6"; Journal of Immunology 147(2):685, July 15, 1991.

-

Lerner, AM et al. A small randomised placebo-controlled trial of the use of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2001, 32, 1657-1658

-

“(ME)CFS is associated with objective underlying biological abnormalities, particularly involving the nervous and immune system. Most studies have found that active infection with HHV-6 – a neurotropic, gliotropic and immunotropic virus – is present more often in patients with (ME)CFS than in healthy control subjects…Moreover, HHV-6 has been associated with many of the neurological and immunological findings in patients with (ME)CFS” Anthony L Komaroff. Journal of Clinical Virology 2006:37:S1:S39-S46.

-

"Assessment of the frequency of HHV6 in CFS was undertaken by the team at Columbia. D Ablashi showed that the majority of 24 patients studied from Incline Village, Nevada had HHV6 infection. HHV6 was detected in the plasma, CSF and PBMCs. The data suggests the presence of cell free infectious virus in the CSF. It was postulated that HHV6 invading the CNS may participate in the neurological manifestations of the disease."

"A poster also presented by Ablashi et al, showed good concordance between reactivation of HHV6 and presence of RnaseL. They could therefore be used together or separately in monitoring response to treatment. 2 patients were treated with ampligen, which inhibited HHV6 replication and upregulated the 2-5a synthetase/RnaseL pathway."

D Ablashi (Columbia University) research papers submitted to the AACFS 5th International Research, Clinical and Patient Conference, 2001 -

Prevalence in the cerebrospinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: human herpes virus 6 and 8; chlamydia species; mycoplasma species; EBV; CMV; and coxsackie virus. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 2001, 9, 1/2, 41-51

- Viral Infection in CFS patients. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 325-327.

-

Torrisi, et al, wrote "The absence of lycoproteins on the cell surface of the infected cells," showing where the virus is hiding and how it infects (Virology, 257, 1999).

-

Wu et al showed how HHV6 can infect human umbilical vein endothelial cells in the J Gen Vir (1998, 79)

-

Landay AL et al. Lancet 1991; 338: 707

-

Detection of Viral Related Sequences in CFS Patients Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 278-282.

| Back to Listing at top of page |

(b) Enteroviruses

Top ME doctors A. Gilliam, Melvin Ramsay, Elizabeth Dowsett, John Richardson of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, W.H. Lyle, Elizabeth Bell, James Mowbray of St Mary’s, Peter Behan and Byron Hyde all believed that the majority of primary M.E. patients fell ill following exposure to an Enterovirus. Dr. John Richardson, a medical doctor based in Newcastle in England treated ME patients from many parts of Britain for over 40 years. He developed an expertise in diagnosing the illness, and became one of the world's foremost experts in ME. He even used autopsy results from dead patients to investigate the illness. He found that Enteroviruses and toxins played a major role in ME, and that this led to immune dysfunction, neurological abnormalities, endocrine dysfunction, and over time to increased risk of cardiac failure, cancers, carcinomas, and other organ failure. He wrote a book about his medical experiences called Enteroviral and Toxin Mediated Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. This book is a classic medical book on the illness, and provides an excellent introduction to ME. Historically, Enterovirus infections mainly target the nervous system, brain, muscles and intestines, all of which abnormal in ME patients.

-

Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach. John K S Chia, Andrew Y Chia.

J Clin Pathol 2007;0:1–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.050054 - The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome. Dr. J. Chia. J Clin Pathol. Nov 2005; 58(11): 1126–1132.

“Enteroviruses are well known causes of acute respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, with tropism for the central nervous system, muscle, and heart. Initial reports of chronic enteroviral infections causing debilitating symptoms in patients with CFS were met with skepticism, and largely forgotten for the past decade … Recent evidence not only confirmed the earlier studies but also clarified the pathological role of viral RNA through antiviral treatment.”

- Acute enterovirus infection followed by myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and viral persistence.Chia J, Chia A, Voeller M, Lee T, Chang R.J.. Clin Pathol. 2010 Feb;63(2):165-8.

- Dr. John Chia, is a world renowned doctor who has successfully treated ME / CFS patients. He has found that Enteroviruses are present in some subgroups of ME / CFS patients and that treating these Enterovirus infections can lead to significant improvement and recovery.

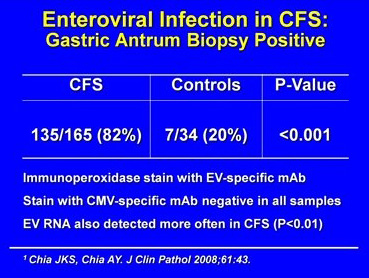

His research paper provides some important insights - Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach. Chia JK, Chia AY. J Clin Pathol. 2008 Jan;61(1):43-8. Epub 2007 Sep 1. See diagram below:

Dr. John Chia presents his research findings up to the year 2011 to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA below:

Video Lecture of medical findings by Dr. John Chia

-

Source: Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003; 36:671–2. Chia.

- Listing of enterovirus research findings and papers - http://www.enterovirusfoundation.org/featuredarticles.shtml

- ME Epidemics

Most ME epidemics mention polio-like viruses, Cocksacke viruses and Enteroviruses. Click here to view listing of research papers from ME epidemics

- Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP) in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is Associated with Chronic Enterovirus Infection of Ovarian Tubes

John Chia, M.D., David Wang, Rabiha El-habbal and Andrew Chia, EV Med Research, Lomita California

IACFS/ME Conference. Translating Science into Clinical Care. March 20-23, 2014 • San Francisco, California, USA

- Pathogenesis of chronic enterovirus infection in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) –in vitro and in vivo studies of infected stomach tissuesJohn Chia, M.D., Andrew Chia, David Wang, Rabiha El-Habbal. EV Med Research. Lomita, CA.

IACFS/ME Conference. Translating Science into Clinical Care. March 20-23, 2014 • San Francisco, California, USA

- Dowsett EG, Ramsay AM, McCartney RA, Bell EJ (1990), "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (M.E.) -- A Persistent Enteroviral Infection?", Postgraduate Medical Journal, 66:526-530

- Kerr JR. Enterovirus infection of the stomach in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J Clin Pathol 2008;61:1e2.

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis: a review with emphasis on key findings in biomedical research. M Hooper. J Clin Pathol. 2007 May; 60(5): 466–471. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.042408

- Lane RJM, Soteriou BA, Zhang H, et al. Enterovirus related metabolic myopathy: a post-viral fatigue syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1382-6.

- Archard LC, Bowles NE, Behan PO, Bell EJ, Doyle D. Postviral fatigue syndrome: persistence of enterovirus RNA in muscle and elevated creatine kinase. J R Soc Med. 1988 Jun;81(6):326-9. PMID: 3404526

- Bell EJ, McCartney RA, Riding MH. Coxsackie B viruses and myalgic encephalomyelitis. J R Soc Med. 1988 Jun;81(6):329-31. PMID: 2841461

- Role of Infection and Neurologic Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Anthony L. Komaroff Tracey A. Cho. Semin Neurol 2011; 31(3): 325-337

- Levine S (2001), "Prevalence in the cerebro spinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: Human Herpes Virus 6 & 8; Chlamydia Species; Mycoplasma Species, EBV; CMV and Coxsackie B Virus", Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 9:91-2:41-51

- Viral Isolation from Brain in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (A Case Report) J. Richardson J. Richardson is affiliated with Newcastle Research Group, Belle Vue, Grange Road, Ryton, Tyne & Wear, NE40 3LU, England. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Vol. 9(3/4) 2001, pp. 15-19

- Chronic enterovirus infection in patients with postviral fatigue syndrome. Yousef GE, Bell EJ, Mann GF, Murugesan V, Smith DG, McCartney RA, Mowbray JF. Lancet. 1988 Jan 23;1(8578):146-50.

- “Enteroviral sequences were found in significantly more ME/CFS patients than in the two comparison groups….This study provides evidence for the involvement of enteroviruses in just under half of the patients presenting with ME/CFS and it confirms and extends previous studies using muscle biopsies. We provide evidence for the presence of viral sequences in serum in over 40% of ME/CFS patients” (J Med Virol 1995:45:156-161)

- " Primary M.E. is always an acute onset illness. Doctors A. Gilliam, A.

Melvin Ramsay and Elizabeth Dowsett (who assisted

in much of his later work,) John Richardson of

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, W.H. Lyle, Elizabeth Bell of

Ruckhill Hospital, James Mowbray of St Mary's, and

Peter Behan all believed that the majority of primary

M.E. patients fell ill following exposure to an Enterovirus. (Poliovirus, ECHO, Coxsackie and the

numbered viruses are the significant viruses in this

group, but there are other enteroviruses that exist that

have been discovered in the past few decades that do

not appear in any textbook that I have perused.) I share

this belief that enteroviruses are a major cause. "

Source: http://www.nightingale.ca/documents/Nightingale_ME_Definition_en.pdf

- Lyle WH. Encephalomyelitis resembling benign myalgic encephalomyelitis. Lancet. 1970 May 23;1(7656):1118-9. PMID: 4191997

- Ramsay AM, Rundle A. Clinical and biochemical findings in ten patients with benign myalgic encephalomyelitis. Postgrad Med J. 1979 Dec;55(654):856-7.

- Ramsay AM, Dowsett EG, Dadswell JV, Lyle WH, Parish JG. Icelandic disease (benign myalgic encephalomyelitis or Royal Free disease) Br Med J. 1977 May 21;1(6072): 1350. PMID: 861618 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1607215/pdf/brmedj00463-0058b.pdf

- Quantitative analysis of viral RNA kinetics in coxsackievirus B3-induced murine myocarditis: biphasic pattern of clearance following acute infection, with persistence of residual viral RNA throughout and beyond the inflammatory phase of disease. Reetoo KN, Osman SA, Illavia SJ, Cameron-Wilson CL, Banatvala JE, Muir P J Gen Virol. 2000 Nov; 81(Pt 11):2755-62.

- Enterovirus related metabolic myopathy: a postviral fatigue syndrome. Lane RJ, Soteriou BA, Zhang H, Archard LC J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 Oct; 74(10):1382-6.

- Spence V A, Khan F, Kennedy G. et al Inflammation and arterial stiffness in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 8th International IACFS Conference on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia and other related illnesses, Fort Lauderdale, Floride, USA, January, 2007

- Bacterial and Viral Co-Infections in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS/ME) Patients. Nicolson et al., Proc. Clinical & Scientific Conference on Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, the Practitioners Challenge, Alison Hunter Foundation, Sydney, Australia 2002

- Parish JG (1978), Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia', Postgraduate Medical Journal, Nov;54(637):711-7, PMID: 370810. 'Epidemic Neuromyasthenia' was used to describe ME in the past.

- Medical and Scientific Books

Enteroviral and Toxin Mediated Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

The Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis--Chronic Fatigue Syndromeby Dr. Jay Goldstein, Dr. Byron Hyde, P. Levine, Nightingale Research Foundation.

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Post Viral Fatigue States: the Saga of the Royal Free Disease by Dr Melvin Ramsay

- In the UK, about 60% of patients with ME / CFS have evidence of

enterovirus infection, most commonly Cocksackie B. This has been

demonstrated by the finding of enterovirus RNA in muscle and in blood.

Many other patients have reactivated Epstein Barr virus. It has not been

verified if the virus itself causes ME / CFS or it is the result of a

weakened immune system.

Source: Action for ME, Britain.

- Enterovirus in the chronic fatigue syndrome. McGarry F, Gow J and Behan PO Ann Intern Med 1994:120:972 973

- The Putative Role of Viruses, Bacteria, and Chronic Fungal Biotoxin Exposure in the Genesis of Intractable Fatigue Accompanied by Cognitive and Physical Disability. Morris et al. 2015

- “Virological studies revealed that 76% of the patients with suspected myalgic encephalomyelitis had elevated Coxsackie B neutralising titres (and symptoms included) malaise, exhaustion on physical or mental effort, chest pain, palpitations, tachycardia, polyarthralgia, muscle pains, back pain, true vertigo, dizziness, tinnitus, nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, epigastric pain, headaches, paraesthesiae, dysuria)….The group described here are patients who have had this miserable illness. Most have lost many weeks of employment or the enjoyment of their family (and) marriages have been threatened…”

(BD Keighley, EJ Bell. JRCP 1983:33:339-341).

- Levine S (2001), "Prevalence in the cerebro spinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: Human Herpes Virus 6 & 8; Chlamydia Species; Mycoplasma Species, EBV; CMV and Coxsackie B Virus", Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 9:91-2:41-51

- Gilliam AG (1938), "Epidemiological Study on an Epidemic, Diagnosed as Poliomyelitis, Occurring among the Personnel of Los Angeles County General Hospital during the Summer of 1934", United States Treasury Department Public Health Service Public Health Bulletin, No. 240, pp. 1-90. Washington, DC, Government Printing Office

- Enteroviral Myalgic Encephalomyelitis - EvME: A treatise on EvME by Dr Irving Spurr

- The outbreak in Iceland was important, and provided some vital clues about the illness and the role of Enteroviruses.

"However, children in epidemic Neuromyasthenia areas responded to poliomyelitis vaccination with higher antibody titres than in other areas not affected by the poliomyelitis epidemic, as if these children had already been exposed to an agent immunologically similar to poliomyelitis virus (Sigurdsson, Gudnad6ttir Petursson, 1958). Thus, the agent responsible for epidemic Neuromyasthenia would appear to be able to inhibit the pathological effects of poliomyelitis infection. When an American airman was affected in the 1955 epidemic and returned home, a similar secondary epidemic occurred in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (Hart, 1969: Henderson and Shelokov, 1959)."

Many outbreaks of ME or epidemic Neuromyasthenia worldwide followed an outbreak of polio virus.

Parish JG (1978), Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia', Postgraduate Medical Journal, Nov;54(637):711-7, PMID: 370810.

- "an

agent

was

repeatedly

transmitted

to

monkeys

from

two

patients

(Pellew

and

Miles,

1955).

When

the

monkeys

were

killed

minute

red

spots

were

observed

along

the

course

of

the

sciatic

nerves.

Microscopically

infiltration

of

nerve

roots

with

lymphocytes

and

mononuclear

cells

was

seen

and

some

of

the

nerve

fibres

showed

patchy

damage

to

the

myelin

sheaths

and

axon

swellings.

Similar

findings

had

been

produced

by

the

transmission

of

an

agent

to

monkeys

from

a

child

with

poliomyelitis

in

Boston,

Massachusetts,

in

1947

(Pappenheimer,

Cheever

and

Daniels,

1951).

How-

ever,

in

these

monkeys

the

changes

were

more

widespread,

involving

the

dorsal

root

ganglia,

cervical

and

lumbar

nerve

roots

and

peripheral

nerves.

Perivascular

collars

of

lymphocytes

and

plasma

cells

were

seen

in

the

cerebral

cortex,

brain

stem

and

cerebellum,

spinal

cord

and

around

blood

vessels

to

the

nerve

roots.

There

was

no

evidence

of

damage

to

the

nerve

cells

in

the

brain

or

spinal

cord.

The

distribution

and

intensity

of

the

lesions

varied

considerably

from

monkey

to

monkey.

This

pathological

picture

of

mild

diffuse

changes

corresponds

closely

to

what

might

be

expected

from

clinical

observations

of

patients

with

neurological

involvement in epidemic Neuromyasthenia

Parish JG (1978), Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia', Postgraduate Medical Journal, Nov;54(637):711-7, PMID: 370810.

- Three

Babuska Clusters of Enteroviral-Associated Myalgic Encephalomyelitis

Nightingale Research Foundation

Paper Presented by Byron Marshall Hyde M.D.

New South Wales, February 1998 -

Hickie I, et al. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. British Journal of Medicine 2006; 333 (7568):575.

-

"Myeloadenamate Deaminase deficiency in muscles of ME patients. It is known that the enzyme is missing after a viral attack"

Professor Peter Behan, The Institute of Neurological Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland. -

“Recently associations have been found between Coxsackie B infection and a more chronic multisystem illness. A similar illness…has been referred to as… myalgic encephalomyelitis…140 patients presenting with symptoms suggesting a postviral syndrome were entered into the study…Coxsackie B antibody levels were estimated in 100 control patients…All the Coxsackie B virus antibody tests were performed blind…Of the 140 ill patients, 46% were found to be Coxsackie B virus antibody positive…This study has confirmed our earlier finding that there is a group of symptoms with evidence of Coxsackie B infection. We have also shown that clinical improvement is slow and recovery does not correlate with a fall in Coxsackie B virus antibody titre” (BD Calder et al. JRCGP 1987:37:11-14).

-

Presence of Viral Protein 1 (VP1)

"There are no tests to confirm a diagnosis, although 60% of sufferers will have a specific protein in their blood called viral protein 1, (VP1)."

Susan Clark, www.whatreallyworks.co.uk - 'Epidemic neuromyasthenia' 1955-1978'. Postgrad Med J. 1978 Nov;54(637):718-21. PMID: 746017

- Anti-pathogen and immune system treatments. Treatment of 741 italian patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. U. TIRELLI, A. LLESHI, M. BERRETTA, M. SPINA, R. TALAMINI, A. GIACALONE. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2013; 17: 2847-2852

- Cunningham L, Bowles NE, Lane RJ, Dubowitz V, and Archard LC: Persistence of Enteroviral RNA in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is Associated with the Abnormal Production of Equal Amounts of Positive and Negative Strands of Enteroviral RNA. J General Virol 1990; 71:1399--1402

-

Findings and Testimony of Burke A. Cunha, MD., chief, infectious disease division, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, N.Y., USA.

"But the most consistent lab evidence that we look for are elevations of coxsackie B-titers and elevations of HHV-6 titers in combination with the decrease in the percentage of natural killer T cells," Cunha explained. "If the patient has two or three of these abnormalities in our study center, then he or she fits the laboratory criteria for chronic fatigue. Nearly all patients with crimson crescents have two out of three of these laboratory abnormalities," he said. -

“These results show that chronic infection with enteroviruses occurs in many PVFS (post-viral fatigue syndrome, a classified synonym for ME/CFS) patients and that detection of enterovirus antigen in the serum is a sensitive and satisfactory method for investigating infection in these patients….Several studies have suggested that infection with enteroviruses is causally related to PVFS…The association of detectable IgM complexes and VP1 antigen in the serum of PVFS patients in our study was high…This suggests that enterovirus infection plays an important role in the aetiology of PVFS” (GE Yousef, EJ Bell, JF Mowbray et al. Lancet January 23rd 1988:146-150).

-

Prevalence in the cerebrospinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: human herpes virus 6 and 8; chlamydia species; mycoplasma species; EBV; CMV; and coxsackie virus. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 2001, 9, 1/2, 41-51

-

Viral Infection in CFS patients. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 325-327.

- "However,

children

in epidemic Neuromyasthenia areas

responded

to

poliomyelitis

vaccination

with

higher

antibody titres

than

in

other

areas

not

affected

by

the

poliomyelitis

epidemic,

as

if

these

children

had

already

been

exposed

to

an

agent

immunologically

similar

to

poliomyelitis

virus

(Sigurdsson,

Gudnad6ttir Petursson,

1958).

Thus,

the

agent

responsible

for

epidemic Neuromyasthenia would

appear

to

be

able

to

inhibit

the

pathological

effects

of

poliomyelitis

infection.

When

an

American

airman

was

affected

in

the

1955

epidemic

and

returned

home,

a

similar

secondary

epidemic

occurred

in

Pittsfield,

Massachusetts,

U.S.A.

(Hart,

1969:

Henderson

and

Shelokov,

1959)."

Parish JG (1978), Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia', Postgraduate Medical Journal, Nov;54(637):711-7, PMID: 370810.

- “Myalgic encephalomyelitis is a common disability but frequently misinterpreted…This illness is distinguished from a variety of other post-viral states by a unique clinical and epidemiological pattern characteristic of enteroviral infection…33% had titres indicative and 17% suggestive of recent CBV infection…Subsequently…31% had evidence of recent active enteroviral infection…There has been a failure to recognise the unique epidemiological pattern of ME…Coxsackie viruses are characteristically myotropic and enteroviral genomic sequences have been detected in muscle biopsies from patients with ME. Exercise related abnormalities of function have been demonstrated by nuclear magnetic resonance and single-fibre electromyography including a failure to coordinate oxidative metabolism with anaerobic glycolysis causing abnormal early intracellular acidosis, consistent with the early fatiguability and the slow recovery from exercise in ME. Coxsackie viruses can initiate non-cytolytic persistent infection in human cells. Animal models demonstrate similar enteroviral persistence in neurological disease… and the deleterious effect of forced exercise on persistently infected muscles. These studies elucidate the exercise-related morbidity and the chronic relapsing nature of ME” (EG Dowsett, AM Ramsay et al. Postgraduate Medical Journal 1990:66:526-530).

-

“The findings described here provide the first evidence that postviral fatigue syndrome may be due to a mitochondrial disorder precipitated by a virus infection…Evidence of mitochondrial abnormalities was present in 80% of the cases with the commonest change (seen in 70%) being branching and fusion of cristae, producing ‘compartmentalisation’. Mitochondrial pleomorphism, size variation and occasional focal vacuolation were detectable in 64%…Vacuolation of mitochondria was frequent…In some cases there was swelling of the whole mitochondrion with rupture of the outer membranes…prominent secondary lysosomes were common in some of the worst affected cases…The pleomorphism of the mitochondria in the patients’ muscle biopsies was in clear contrast to the findings in normal control biopsies…Diffuse or focal atrophy of type II fibres has been reported, and this does indicate muscle damage and not just muscle disuse” (WMH Behan et al. Acta Neuropathologica 1991:83:61-65).

- “Persistent enteroviral infection of muscle may occur in some patients with postviral fatigue syndrome and may have an aetiological role….The features of this disorder suggest that the fatigue is caused by involvement of both muscle and the central nervous system…We used the polymerase chain reaction to search for the presence of enteroviral RNA sequences in a well-characterised group of patients with the postviral fatigue syndrome…53% were positive for enteroviral RNA sequences in muscle…Statistical analysis shows that these results are highly significant…On the basis of this study…there is persistent enteroviral infection in the muscle of some patients with the postviral fatigue syndrome and this interferes with cell metabolism and is causally related to the fatigue” (JW Gow et al. BMJ 1991:302:696-696).

-

“Postviral fatigue syndrome / myalgic encephalomyelitis… has attracted increasing attention during the last five years…Its distinguishing characteristic is severe muscle fatiguability made worse by exercise…The chief organ affected is skeletal muscle, and the severe fatiguability, with or without myalgia, is the main symptom. The results of biochemical, electrophysiological and pathological studies support the view that muscle metabolism is disturbed, but there is no doubt that other systems, such as nervous, cardiovascular and immune are also affected…Recognition of the large number of patients affected…indicates that a review of this intriguing disorder is merited….The true syndrome is always associated with an infection…Viral infections in muscle can indeed be associated with a variety of enzyme abnormalities…(Electrophysiological results) are important in showing the organic nature of the illness and suggesting that muscle abnormalities persist after the acute infection…there is good evidence that Coxsackie B virus is present in the affected muscle in some cases” (PO Behan, WMH Behan. CRC Crit Rev Neurobiol 1988:4:2:157-178).

-

“The main features (of ME) are: prolonged fatigue following muscular exercise or mental strain, an extended relapsing course; an association with neurological, cardiac, and other characteristic enteroviral complications. Coxsackie B neutralisation tests show high titres in 41% of cases compared with 4% of normal adults…These (chronic enteroviral syndromes) affect a young, economically important age group and merit a major investment in research” (EG Dowsett. Journal of Hospital Infection 1988:11:103-115).

- The impact of persistent enteroviral infection by Dr. Betty Dowsett

- “Ten patients with post-viral fatigue syndrome and abnormal serological, viral, immunological and histological studies were examined by single fibre electromyographic technique….The findings confirm the organic nature of the disease. A muscle membrane disorder…is the likely mechanism for the fatigue and the single-fibre EMG abnormalities. This muscle membrane defect may be due to the effects of a persistent viral infection…There seems to be evidence of a persistent viral infection and/or a viral-induced disorder of the immune system…The infected cells may not be killed but become unable to carry out differentiated or specialised function” (Goran A Jamal, Stig Hansen. Euro Neurol 1989:29:273-276).

-

An Outbreak of Encephalomyelitis in the Royal Free Hospital Group, London, in 1955 by THE MEDICAL STAFF OF THE ROYAL FREEHOSPITAL in British Medical Journal in 1957.

-

'Epidemic Neuromyasthenia. An outbreak of poliomyelitis-like illness in student nurses' published in the New England Journal of Medicine

-

Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis. Galpine, J.F. Brit. J. Clin. Practice, 12: 186, 1958.

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Guidelines for Doctors Journal: J of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Vol. 10(1) 2002, John Richardson, MB BS

- “Molecular viral studies have recently proved to be extremely useful. They have confirmed the likely important role of enteroviral infections, particularly with Coxsackie B virus” (Postviral fatigue syndrome: Current neurobiological perspective. PGE Kennedy. BMB 1991:47:4:809-814)

- In his Summary of the Viral Studies of CFS, Dr Dharam V Ablashi concluded: “The presentations and discussions at this meeting strongly supported the hypothesis that CFS may be triggered by more than one viral agent…Komaroff suggests that, once reactivated, these viruses contribute directly to the morbidity of CFS by damaging certain tissues and indirectly by eliciting an on-going immune response”(Clin Inf Dis 1994:18 (Suppl 1):S130-133). It is recommended that the entire 167-page Journal be read

- “Our focus will be on the ability of certain viruses to interfere subtly with the cell’s ability to produce specific differentiated products as hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines and immunoglobulins etc in the absence of their ability to lyse the cell they infect. By this means viruses can replicate in histologically normal appearing cells and tissues…Viruses by this means likely underlie a wide variety of clinical illnesses, currently of unknown aetiology, that affect the endocrine, immune, nervous and other …systems” (JC de la Torre, P Borrow, MBA Oldstone. BMB 1991:47:4:838-851).

-

“We conclude that persistent enteroviral infection plays a role in the pathogenesis of PVFS…The strongest evidence implicates Coxsackie viruses…Patients with PVFS were 6.7 times more likely to have enteroviral peristence in their muscles” (JW Gow and WMH Behan. BMB 1991:47:4:872-885).

-

“The postviral fatigue syndrome (PVFS), with profound muscle fatigue on exertion and slow recovery from exhaustion seems to be related specifically to enteroviral infection. The form seen with chronic reactivated EBV infection is superficially similar, but without the profound muscle fatigue on exercise” (JF Mowbray, GE Yousef. BMB 1991:47:4:886-894).

- A New and Simple Definition of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and a New Simple Definition of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome & A Brief History of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis & An Irreverent History of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Dr Byron Hyde 2006

-

“Skeletal samples were obtained by needle biopsy from patients diagnosed clinically as having CFS (and) most patients fulfilled the criteria of the Centres for Disease Control for the diagnosis of CFS (Holmes et al 1988)…These data are the first demonstration of persistence of defective virus in clinical samples from patients with CFS…We are currently investigating the effects of persistence of enteroviral RNA on cellular gene expression leading to muscle dysfunction” (L Cunningham, RJM Lane, LC Archard et al. Journal of General Virology 1990:71:6:1399-1402).

-

“These results suggest there is persistence of enterovirus infection in some CFS patients and indicate the presence of distinct novel enterovirus sequences…Several studies have shown that a significant proportion of patients complaining of CFS have markers for enterovirus infection….From the data presented here…the CFS sequences may indicate the presence of novel enteroviruses…It is worth noting that the enteroviral sequences obtained from patients without CFS were dissimilar to the sequences obtained from the CFS patients…This may provide corroborating evidence for the presence of a novel type of enterovirus associated with CFS” (DN Galbraith, C Nairn and GB Clements. Journal of General Virology 1995:76:1701-1707).

-

“We will report at the First International Research Conference on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome to be held at Albany, New York, 2-4 October 1992, our new findings relating particularly to enteroviral infection…We have isolated RNA from patients and probed this with large enterovirus probes…detailed studies...showed that the material was true virus…Furthermore, this virus was shown to be replicating normally at the level of transcription. Sequence analysis of this isolated material showed that it had 80% homology with Coxsackie B viruses and 76% homology with poliomyelitis virus, demonstrating beyond any doubt that the material was enterovirus” (Press Release for the Albany Conference, Professor Peter O Behan, University of Glasgow, October 1992).

-

“In the CFS study group, 42% of patients were positive for enteroviral sequences by PCR, compared to only 9% of the comparison group…Enteroviral PCR does, however, if positive, provide evidence for circulating viral sequences, and has been used to show that enteroviral specific sequences are present in a significantly greater proportion of CFS patients than other comparison groups” (C Nairn et al. Journal of Medical Virology 1995:46:310-313).

-

“Samples from 25.9% of the PFS (postviral fatigue syndrome) were positive for the presence of enteroviral RNA, compared with only 1.3% of the controls…We propose that in PFS patients, a mutation affecting control of viral RNA synthesis occurs during the initial phase of active virus infection and allows persistence of replication defective virus which no longer attracts a cellular immune response” (NE Bowles, RJM Lane, L Cunningham and LC Archard. Journal of Medicine 1993:24:2&3:145-180).

-

“These data support the view that while there may commonly be asyptomatic enterovirus infections of peripheral blood, it is the presence of persistent virus in muscle which is abnormal and this is associated with postviral fatigue syndrome…Evidence derived from epidemiological, serological, immunological, virological, molecular hybridisation and animal experiments suggests that persistent enteroviral infection may be involved in… PFS” (PO Behan et al. CFS: CIBA Foundation Symposium 173, 1993:146-159).

-

Seeking to detect and characterise enterovirus RNA in skeletal muscle from patients with (ME)CFS and to compare efficiency of muscle metabolism in enterovirus positive and negative (ME)CFS patients, Lane et al obtained quadriceps biopsy samples from 48 patients with (ME)CFS. Muscle biopsy samples from 20.8% of patients were positive, while 100% of the controls were negative for enterovirus sequences. Lane et al concluded: “There is an association between abnormal lactate response to exercise, reflecting impaired muscle energy metabolism, and the presence of enterovirus sequences in muscle in a proportion of (ME)CFS patients” (RJM Lane, LC Archard et al. JNNP 2003:74:1382-1386).

-

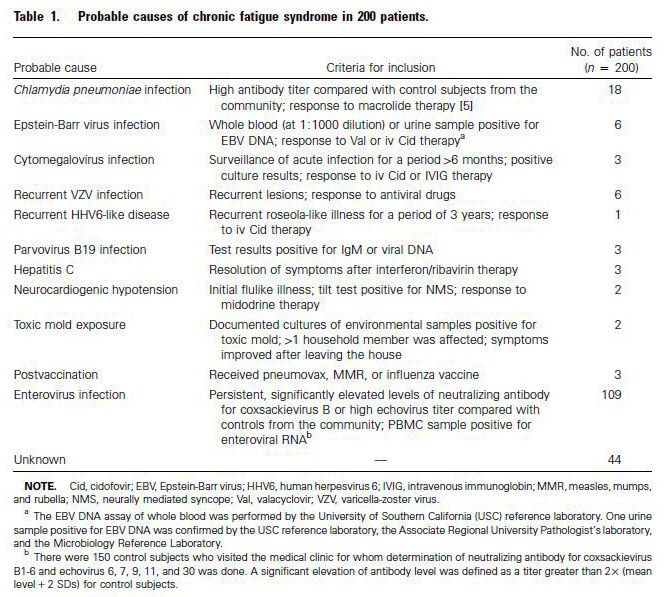

Kerr et al then go on to provide evidence of other triggers of (ME)CFS which include Parvovirus; C. pneumoniae; C. burnetti; toxin exposure and vaccination including MMR, pneumovax, influenza, hepatitis B, tetanus, typhoid and poliovirus (LD Devanur, JR Kerr. Journal of Clinical Virology 2006: 37(3):139-150).

-

“Research studies have identified various features relevant to the pathogenesis of CFS/ME such as viral infection, immune abnormalities and immune activation, exposure to toxins, chemicals and pesticides, stress, hypotension…and neuroendocrine dysfunction….Various viruses have been shown to play a triggering or perpetuating role, or both, in this complex disease….The role of enterovirus infection as a trigger and perpetuating factor in CFS/ME has been recognised for decades…The importance of gastrointestinal symptoms in CFS/ME and the known ability of enteroviruses to cause gastrointestinal infections led John and Andrew Chia to study the role of enterovirus infection in the stomach of CFS/ME patients…They describe a systematic study of enterovirus infection in the stomach of 165 CFS/ME patients, demonstrating a detection rate of enterovirus VP1 protein in 82% of patients…the possibility of an EV outbreak…seems unlikely, as these patients developed their diseases at different times over a 20 year period” (Jonathan R Kerr. Editorial. J Clin Pathol 14th September 2007. Epub ahead of print).

-

“Since most (ME)CFS patients have persistent or intermittent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, the presence of viral capsid protein 1 (VP1), enterovirus RNA and culturable virus in the stomach biopsy specimens of patients with (ME)CFS was evaluated…Our recent analysis of 200 patients suggests that… enteroviruses may be the causative agents in more than half of the patients…At the time of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, the majority of patients had mild, focal inflammation in the antrum…95% of biopsy specimens had microscopic evidence of mild chronic inflammation…82% of biopsy specimens stained positive for VP1 within parietal cells, whereas 20% of the controls stained positive…An estimated 80-90% of our 1,400 (ME)CFS patients have recurring gastrointestinal symptoms of varying severity, and epigastric and/or lower quadrant tenderness by examination…Finding enterovirus protein in 82% of stomach biopsy samples seems to correlate with the high percentage of (ME)CFS patients with GI complaints…Interestingly, the intensity of VP1 staining of the stomach biopsy correlated inversely with functional capacity…A significant subset of (ME)CFS patients may have a chronic, disseminated, non-cytolytic form of enteroviral infection which can lead to diffuse symptomatology without true organ damage” (Chia JK, Chia AY. J Clin Pathol 13th September 2007 Epub ahead of print).

-

In a review of the role of enteroviruses in (ME)CFS, Chia noted that initial reports of chronic enteroviral infections causing debilitating symptoms in (ME)CFS patients were met with scepticism and largely forgotten, but observations from in vitro experiments and from animal models clearly established a state of chronic persistence through the formation of double stranded RNA, similar to findings reported in muscle biopsies of patients with (ME)CFS. Recent evidence not only confirmed the earlier studies, but also clarified the pathogenic role of viral RNA (JKS Chia. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2005:58:1126-1132).

-

Torrisi, et al, wrote "The absence of lycoproteins on the cell surface of the infected cells," showing where the virus is hiding and how it infects (Virology, 257, 1999).

-

Detection of Viral Related Sequences in CFS Patients Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 278-282.

- As mentioned elsewhere, researchers from the Enterovirus Research Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Centre wrote a specially-commissioned explanatory article for the UK charity Invest in ME, in which they stated that human enteroviruses were not generally thought to persist in the host after an acute infection, but they had discovered that Coxsackie B viruses can naturally delete sequence from the 5’ end of the RNA genome, and that this results in long-term viral persistence, and that “This previously unknown and unsuspected aspect of enterovirus replication provides an explanation for previous reports of enteroviral RNA detected in diseased tissue in the apparent absence of infectious virus particles” (S Tracy and NM Chapman. Journal of IiME 2009:3:1).

(http://www.investinme.org/Documents/Journals/Journal%20of%20IiME%20Vol%203%20Issue%201.pdf). -

“Recent developments in molecular biology…have revealed a hitherto unrecognised association between enteroviruses and some of the most disabling, chronic and disheartening neurological, cardiac and endocrine diseases…Persistent infection (by enteroviruses) is associated with ME/CFS…The difficulty of making a differential diagnosis between ME/CFS and post-polio sequelae cannot be over-emphasised…(EG Doswett. Commissioned for the BASEM meeting at the RCGP, 26th April 1998:1-10).

-

“To prove formally that persistence rather than re-infection is occurring, it is necessary to identify a unique feature retained by serial viral isolates from one individual. We present here for the first time evidence for enteroviral persistence (in humans with CFS)…” (DN Galbraith et al. Journal of General Virology 1997:78:307-312).

| Back to Listing at top of page |

(c) Epstein Barr virus & Herpes family viruses, including reactivation of latent herpes viruses (EBV, CMV and HHV6a)

- Deficient EBV-specific B- and T-cell response in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Loebel M, Strohschein K, Giannini C, Koelsch U, Bauer S, Doebis C, Thomas S, Unterwalder N, von Baehr V, Reinke P, Knops M, Hanitsch LG, Meisel C, Volk HD, Scheibenbogen

Scientific analysis and discussion on http://simmaronresearch.com/2014/03/1591/

- Hickie I, et al. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. British Journal of Medicine 2006; 333 (7568):575. Eriksen W. Med Hypotheses. 2017 May;102:8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.02.011. Epub 2017 Feb 28.

- The spread of EBV to ectopic lymphoid aggregates may be the final common pathway in the pathogenesis of ME/CFS

- Tobi M, Morag A, Ravid Z, Chowers I, Feldman-Weiss V, Michaeli Y, Ben-Chetrit E, Shalit M, Knobler H: Prolonged atypical illness associated with serological evidence of persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection. Lancet 1982, 1:61-64.

- Could the Epstein-Barr Virus – Autoimmunity Hypothesis Help Explain Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ? and

EBV I: A Deficient Immune Response, Increased Levels of Epstein-Barr Virus Opens Up EBV Question in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Again Simmaron Research, USA

- A subset of ME / CFS patients have been found to have EBV infection - "There is prolonged elevated antibody level against the encoded proteins EBV dUTPase and EBV DNA polymerase in a subset of CFS patients, suggesting that this antibody panel could be used to identify these patients." Antibody to Epstein-Barr Virus Deoxyuridine Triphosphate Nucleotidohydrolase and Deoxyribonucleotide Polymerase in a Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Subset. A. Martin Lerner, Maria E. Ariza, Marshall Williams, Leonard Jason, Safedin Beqaj, James T. Fitzgerald, Stanley Lemeshow, Ronald Glaser

- Childhood 'kissing disease' linked to adult chronic illnesses. 11 Alive News, USA, December 2016.

- Abortive lytic Epstein–Barr virus replication in tonsil-B lymphocytes in infectious mononucleosis and a subset of the chronic fatigue syndrome. A Martin Lerner, Safedin Beqaj. Virus Adaptation and Treatment November 2012 Volume 2012:4 Pages 85 - 91.

- Valacyclovir treatment in Epstein-Barr virus subset chronic fatigue syndrome: thirty-six months follow-up. Lerner AM, Beqaj SH, Deeter RG, Fitzgerald JT. In Vivo. 2007 Sep-Oct;21(5):707-13.

- The Putative Role of Viruses, Bacteria, and Chronic Fungal Biotoxin Exposure in the Genesis of Intractable Fatigue Accompanied by Cognitive and Physical Disability. Morris et al. 2015

- Lerner M, Beqaj S, Fitzgerald JT, Gill K, Gill C, Edington J (2010), "Subset-directed antiviral treatment of 142 herpesvirus patients with chronic fatigue syndrome", Virus Adaptation and Treatment, mei, Volume 2010:2, p.47-57,

- Knox, K., et al. Systemic Leukotropic Herpesvirus Infections and Autoantibodies in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 7th International Conference on HHV-6 and 7. March 1, 2011. Reston, VA.

- Agliari E, Barra A, Vidal KG, Guerra F (2012), "Can persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection induce chronic fatigue syndrome as a Pavlov reflex of the immune response?", J Biol Dyn 6(2):740-62

- Magnusson M, Brisslert M, Zendjanchi K, Lindh M, Bokarewa MI (2010), "Epstein-Barr virus in bone marrow of rheumatoid arthritis patients predicts response to rituximab treatment", Rheumatology (Oxford), Oct;49(10):1911-9, Epub 2010 Jun 14

- “Over the last decade a wide variety of infectious agents has been associated with CFS by researchers from all over the world. Many of these agents are neurotrophic and have been linked to other diseases involving the central nervous system (CNS)…Because patients with CFS manifest a wide range of symptoms involving the CNS as shown by abnormalities on brain MRIs, SPECT scans of the brain and results of tilt-table testing, we sought to determine the prevalence of HHV-6, HHV-8, EBV, CMV, Mycoplasma species, Chlamydia species and Coxsackie virus in the spinal fluid of a group of patients with CFS. Although we intended to search mainly for evidence of actively replicating HHV-6, a virus that has been associated by several researchers with this disorder, we found evidence of HHV-8, Chlamydia species, CMV and Coxsackie virus in (50% of patient) samples…It was also surprising to obtain such a relatively high yield of infectious agents on cell free specimens of spinal fluid that had not been centrifuged” (Susan Levine. JCFS 2002:9:1/2:41-51).

- Katz BZ , Shiraishi Y , Mears CJ , Binns HJ , Taylor R . Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009 Jul;124(1):189-93. PMID: 19564299

- Loebel M, Strohschein K, Giannini C, Koelsch U, Bauer S, Doebis C, Thomas S, Unterwalder N, Von Baehr V, Reinke P, Knops M, Hanitsch LG, Meisel C, Volk H-D, Scheibenbogen C (2014), "Deficient EBV-Specific B- and T-Cell Response in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", PLoS ONE 9(1): e85387

- Vojdani A

,

Lapp CW

. Interferon-induced proteins are elevated in blood samples of

patients with chemically or virally induced chronic fatigue syndrome. Immunopharmacol

Immunotoxicol. 1999 May;21(2):175-202. PMID: 10319275

Certain toxic chemicals and certain viruses produce the same kinds of inflammatory effects and defects in 2-5A Synthetase and Protein Kinase RNA (PKR)). Anti IFN beta inhibited the reactions.

. - Shapiro JS (2009), "Does varicella-zoster virus infection of the peripheral ganglia cause Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?", Medical Hypotheses Volume 73, Issue 5, November 2009, Pages 728-734, PMID: 19520522,

- There was evidence for ongoing infections with herpes viruses. A subset of patients (those with onset associated with EBV and those with recurrent herpes lesions) who improved on valaciclovir. She recommends trying a course in these patients. Some patients may have ongoing EBV activation. (Invest in ME Scientific Conference, 2013 Professor Carmen Scheibenbogen, Berlin,Germany)

- Levine S (2001), "Prevalence in the cerebro spinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: Human Herpes Virus 6 & 8; Chlamydia Species; Mycoplasma Species, EBV; CMV and Coxsackie B Virus", Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 9:91-2:41-51

- Agliari E, Barra A, Vidal KG, Guerra F (2012), "Can persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection induce chronic fatigue syndrome as a Pavlov reflex of the immune response?", J Biol Dyn 6(2):740-62,

- “…from an immunological point of view, patients with chronic active EBV infection appear ‘frozen’ in a state typically found only briefly during convalescence from acute EBV infection” (G Tosato, S Straus et al. The Journal of Immunology 1985:134:5:3082-3088.)

- Freeman ML, Burkum CE, Jensen MK, Woodland DL, Blackman MA(2012), "γ-Herpesvirus Reactivation Differentially Stimulates Epitope-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses", Immunology, 2012 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102787,

- In his Summary of the Viral Studies of CFS, Dr Dharam V Ablashi concluded: “The presentations and discussions at this meeting strongly supported the hypothesis that CFS may be triggered by more than one viral agent…Komaroff suggests that, once reactivated, these viruses contribute directly to the morbidity of CFS by damaging certain tissues and indirectly by eliciting an on-going immune response”(Clin Inf Dis 1994:18 (Suppl 1):S130-133). It is recommended that the entire 167-page Journal be read

- Prevalence of abnormal cardiac wall motion in the cardiomyopathy associated with incomplete multiplication of Epstein-Barr virus and/or cytomegalovirus in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Lerner et al. In Vivo, 18:417-424 (2004)

- “Ninety percent of the patients tested had antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus and 45% tested had antibodies to cytomegalovirus…if this fatigue syndrome is triggered by an infectious agent, an abnormal immune response may be involved” (TJ Marrie et al. Clinical Ecology 1987:V:1:5-10).

- Robertson ES (red.) (2010), "Epstein-Barr Virus: Latency and Transformation", Caister Academic Press, april, ISBN 978-1-904455-64-6

- In the UK, about 60% of patients with ME / CFS have evidence of

enterovirus infection, most commonly Cocksackie B. This has been

demonstrated by the finding of enterovirus RNA in muscle and in blood.

Many other patients have reactivated Epstein Barr virus. It has not been

verified if the virus itself causes ME / CFS or it is the result of a

weakened immune system.

Source: Action for ME, Britain.

- Bacterial and Viral Co-Infections in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS/ME) Patients. Nicolson et al., Proc. Clinical & Scientific Conference on Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, the Practitioners Challenge, Alison Hunter Foundation, Sydney, Australia 2002

- Role of Infection and Neurologic Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Anthony L. Komaroff Tracey A. Cho. Semin Neurol 2011; 31(3): 325-337

- Prevalence in the cerebrospinal fluid of the following infectious agents in a cohort of 12 CFS subjects: human herpes virus 6 and 8; chlamydia species; mycoplasma species; EBV; CMV; and coxsackie virus. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 2001, 9, 1/2, 41-51

- Jason LA, Sorenson M, Porter N, Belkairous N (2010), "An Etiological Model for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome", Neuroscience & Medicine, 2011, 2, 14-27, PMID: 21892413

- Anti-pathogen and immune system treatments. Treatment of 741 italian patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. U. TIRELLI, A. LLESHI, M. BERRETTA, M. SPINA, R. TALAMINI, A. GIACALONE. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2013; 17: 2847-2852

- Hickie I. et al. BMJ, 2006: 333: 575-580.

- "Myeloadenamate Deaminase deficiency in muscles of ME patients. It is

known that the enzyme is missing after a viral attack"

Professor Peter Behan, The Institute of Neurological Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland.

- Presence of Viral Protein 1 (VP1)

"There are no tests to confirm a diagnosis, although 60% of sufferers will have a specific protein in their blood called viral protein 1, (VP1)."

Susan Clark, www.whatreallyworks.co.uk

- "an

agent

was

repeatedly

transmitted

to

monkeys

from

two

patients

(Pellew

and

Miles,

1955).

When

the

monkeys

were

killed

minute

red

spots

were

observed

along

the

course

of

the

sciatic

nerves.

Microscopically

infiltration

of

nerve

roots

with

lymphocytes

and

mononuclear

cells

was

seen

and

some

of

the

nerve

fibres

showed

patchy

damage

to

the

myelin

sheaths

and

axon

swellings.

Similar

findings

had

been

produced

by

the

transmission

of

an

agent

to

monkeys

from

a

child

with

poliomyelitis

in

Boston,

Massachusetts,

in

1947

(Pappenheimer,

Cheever

and

Daniels,

1951).

How-

ever,

in

these

monkeys

the

changes

were

more

widespread,

involving

the

dorsal

root

ganglia,

cervical

and

lumbar

nerve

roots

and

peripheral

nerves.

Perivascular

collars

of

lymphocytes

and

plasma

cells

were

seen

in

the

cerebral

cortex,

brain

stem

and

cerebellum,

spinal

cord

and

around

blood

vessels

to

the

nerve

roots.

There

was

no

evidence

of

damage

to

the

nerve

cells

in

the

brain

or

spinal

cord.

The

distribution

and

intensity

of

the

lesions

varied

considerably

from

monkey

to

monkey.

This

patho-

logical

picture

of

mild

diffuse

changes

corresponds

closely

to

what

might

be

expected

from

clinical

observations

of

patients

with

neurological

involvement in epidemic Neuromyasthenia

Parish JG (1978), Early outbreaks of 'epidemic neuromyasthenia', Postgraduate Medical Journal, Nov;54(637):711-7, PMID: 370810. - Viral Infection in CFS patients. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 325-327.

- Torrisi, et al, wrote "The absence of lycoproteins on the cell surface of the infected cells," showing where the virus is hiding and how it infects (Virology, 257, 1999).

- Detection of Viral Related Sequences in CFS Patients Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction. The Clinical and Scientific Basis of ME / CFS, Byron M. Hyde M.D., Ed., The Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992, 278-282.

(d) Retrovirus - HTLV viruses, HGRV virus, MLV''s, JHK virus, HIV Negative AIDS

-

Lipkin / Hornig Chronic Fatigue Initaitive Study in Septmner 2013 found that 85% of patients had evidence of Retroviral infection and 65% had evidence of Annellovirus infection

-

DeFreitas E, Hilliard E, Cheney PR, et al. Retroviral Sequences Related to Human T lymphocytotropic virus Type II in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1991;88:2922-2926.

- The world patent entitled "Method and Compositions for Diagnosing and Treating Chronic Fatigue Immunodysfunction Syndrome" #WO9205760 issued to Elaine DeFreitas and Brendan Hilliard, inventors assigned to Wistar Institute, USA. This patent was applied for in August 1991. It concerns the discovery of a new virus the CAV virus which may lie at the root of CFS / ME

- HTLV virus found in CFS patients, infection rates range from 50-75% among CFS patients. HTLV has been found to infect macrophages, B-cells and T-cells.

Research cited in Osler's Web: Inside the Labyrinth of the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Epidemic

by Hillary Johnson, penguin books, 1997, pages 285, 290-291, 352-353.

- Plague: One Scientist?s Intrepid Search for the Truth about Human Retroviruses and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Autism, and Other Diseases

by Dr. Judy Mikovits and Kent Heckenlively

Some excerpts from book http://www.plaguethebook.com/the-promise-and-peril-of-big-science.html and

http://www.plaguethebook.com/asd--an-acquired-immune-deficiency.html

- Palca J (September 14, 1990). "Does a retrovirus explain fatigue syndrome puzzle?". Science 249 (4974): .

- Relationships Between Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type II (HTLV-2)

and Human Lymphotropic Herpes viruses in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Project

funded by The National CFIDS Foundation, Inc.; Needham, Massachusetts

- Detection of MLV-related virus gene sequences in blood of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy blood donors. Harvey J. Alter et al. PNAS, vol. 107 no. 36, 2010. http://www.pnas.org/content/107/36/15874.abstract?tab=author-info

- Detection of MLV-like gag sequences in blood samples from a New York state CFS cohort. Hanson et al. Retrovirology. 2011; 8(Suppl 1): A234.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3112714/

- Dr. Michael Holmes of the Department of Microbiology of the University of Otago (New Zealand) carried out detailed studies into a

CFS-like illness in New Zealand in the 1980's and 1990's. He found evidence of retrovirus infection in most samples and electron microscope pictures of cells with convoluted nuclei similar to AIDS patients. This indicated infection with a retrovirus. He also found evidence of excessive interferon levels, which are linked to retrovirus infection. His findings suggest that a retrovirus was responsible and that there is also significant immune dysfunction in

CFS.

Reported in the book 'Oslers Web', by Hillary Johnson, Penguin Books 1997, pages 661-663

Chapter 33: A Retrovirus Aetiology for CFS?, Michael J. Holmes, M.D from the book The Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis--Chronic Fatigue Syndromeby Dr. Jay Goldstein, Dr. Byron Hyde, P. Levine, Nightingale Research Foundation.

Dr Michael Holmes wrote in The Clinical and Scientific Basis for Myalgic Enchelphalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (1/97) that "structures consistent in size, shape and character with various stages of a Lentivirus (retrovirus) replicative cycle were observed by electron microscopy in cultures from CFS patients..."

Some Papers by Dr. Michael Holmes

Electron microscopic immunocytological profiles in chronic fatigue syndrome. Holmes MJ, Diack DS, Easingwood RA, Cross JP, Carlisle B. J Psychiatr Res. 1997 Jan-Feb;31(1):115-22.

Epidemic neuromyasthenia and chronic fatigue syndrome in west Otago, New Zealand. A 10-year follow-up. Levine PH, Snow PG, Ranum BA, Paul C, Holmes MJ. Arch Intern Med. 1997 Apr 14;157(7):750-4.